This week, we come to the third and final instalment of ‘A Deep Dive into Oolongs’ workshop series by TeeMaa. Each week focussed on a different Oolong producing region including its history, processing, cultivars, brewing and tea tasting. We started off in Guangdong, China before moving across to Taiwan, and finally back to the birthplace of Oolong tea, Wuyi Shan (Wuyi Mountain) in Fujian.

Workshop #3: Cliff Oolong from Wuyi, Fujian, China

Wuyi Cliff Oolong also goes by the name of Wuyi Rock Oolong, Wuyi Rock tea, or Wuyi Yan Cha. For me, Wuyi Cliff Oolongs are the hardcore ones. I’ve dabbled before in their rocky charms, but as our tea guide, Xin Yuan says, they can take many years to get to know. It’s like a slow burn love affair. They’re complex, challenging, sometimes hard to love. It takes patience to fully appreciate their charm.

Origins of Wuyi Cliff Oolong tea

Wuyi tea can be traced back to the Northern and Southern dynasties in China (386 - 589 AD), when historical texts made reference to them as tribute teas for the Emperor. However, it wasn’t always Oolong tea. Wuyi Shan is widely accepted as the birthplace of Red tea (or Black tea as called in the West). The first Red tea to be produced was Lapsang Souchong, created around the beginning of the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), and mainly for export to Europe. Another famous Red tea from the area is Jin Jun Mei (Beautiful Golden Eyebrow).

Wuyi Cliff Oolongs weren’t developed until around the end of the Qing Dynasty. In the early to mid 19th century the British began Red tea production in India, in a bid to break the Chinese monopoly over tea. Red teas from India as well as Sri Lanka and Indonesia became more prominent and prospered on the tea market. And so Oolong tea processing was invented in Wuyi Shan. To protect the tea growing area, Wuyi Shan was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999.

Wuyi Shan Terroir

Wuyi Shan is in Northern Fujian, and its environment is a key factor in the tea’s unique flavour and style. Its landscape is formed of towering peaks soaring above 1,000m and steep gorges, along with mountain streams. The tea bushes grow amid these peaks in the valleys and on the cliffside, benefitting from the natural shade of the mountains with an average 100 days of fog annually.

It has a temperate climate, with average temperatures hovering around 18C and relative humidity of 80%. Wuyi Shan benefits from a unique microclimate created by cold winds from the north and a warm coastal wind from the south.

The Wuyi Shan area is composed of volcanic, gravelly sandstone and shale. Its soil is rich in minerals with excellent drainage, and imparts a unique flavour and complexity to the tea.

Not all Wuyi Cliff Oolongs are from the within the protected national park area. They can be categorised by three types of location:

Zheng Yan, meaning ‘True Cliff’ or ‘True Rock’, is tea that is grown inside the valleys and hills of the Wuyi Shan national park area. These teas have the typical mineral character and last for many infusions. They are the most expensive of the Cliff Oolongs.

Ban Yan, meaning ‘Half Rock’, tea is grown on the outskirts of the national park. It displays less of the rock character and has less body. However, can be more fragrant and is more affordable!

Zhou Cha refers to tea grown in the Wuyi region on flatter land. It’s made in the Cliff Oolong style and tends to be of lower quality.

Cliff Oolong Cultivars and Legends

There are hundreds of different Cliff Oolong cultivars. However there are the four famous ones, and each comes with its own legend.

Da Hong Pao

Da Hong Pao (Big Red Robe / The Emperor’s Crimson Robe) is the most famous of the Cliff Oolongs. The original tea bush is protected and no longer picked for commercial use. Apparently there is even a hut with a permanent member of staff there to guard it!

credit: www.teavivre.com

According to legend, a scholar was on his way to sit the imperial exam. High scores on the imperial exam led to a career as high-ranking official, advising the Emperor. On the way he fell ill in Wuyi Shan. A passing monk from the local temple served him some tea which fully restored him to health. He was then able to make it to the exam, passed with the highest grade, and was awarded an imperial scarlet red robe. Feeling very grateful, he went back to thank the monk and ask him about the tea. When he visited the tea bushes the scholar wrapped his red robe around the tea plant out of gratitude and sent some of the tea back to the palace.

A second part of the story is about the ailing Emperor’s mother. After many doctors had failed to cure her, a scholar (perhaps the same one) gave her some tea to drink. Of course, her health gradually improved and the Emperor ordered that the tea bushes from which this tea was from, be reserved as a tribute tea for the imperial family. Every year the Emperor’s servants would visit the tea bush and hang red robes upon it.

Spiced fried sunflower seeds tea snack at the tea tasting

Shui Jin Gui

The legend of Shui Jin Gui (Golden Water Tortoise) is one of a discontented turtle god. After thousands of years of meditation this turtle achieved godhood, but he soon felt underappreciated. He felt that his hard work and efforts as Heaven’s Tea Gardener went unnoticed. One morning, he awoke to the sounds of the tea farmers celebrating the first flush harvest of tea leaves. Seeing this, he realised that he would be better appreciated as a tea plant, and so gave up his immortality to become the Shui Jin Gui tea plant.

Tie Luo Han

Tie Luo Han (Iron Arhat or Iron Warrior Monk) is believed to be the earliest Wuyi tea, first found in a cave on the cliffs of Wuyi Shan. Legend has it that this tea was created by a powerful warrior monk with golden bronze skin.

Bai Ji Guan

According to legend, the name Bai Ji Guan (White Cockscomb), was given to this tea by a monk in memorial of a courageous rooster that sacrificed his life to protect his baby from an eagle. To honour such a display of courage and love, the monk buried the rooster, and from that very spot the Bai Ji Guan tea bush grew.

Tea Tasting

We tasted 5 Wuyi Cliff Oolongs: the most famous one, Da Hong Pao, as well as an aged Da Hong Pao, plus three other lesser known cultivars.

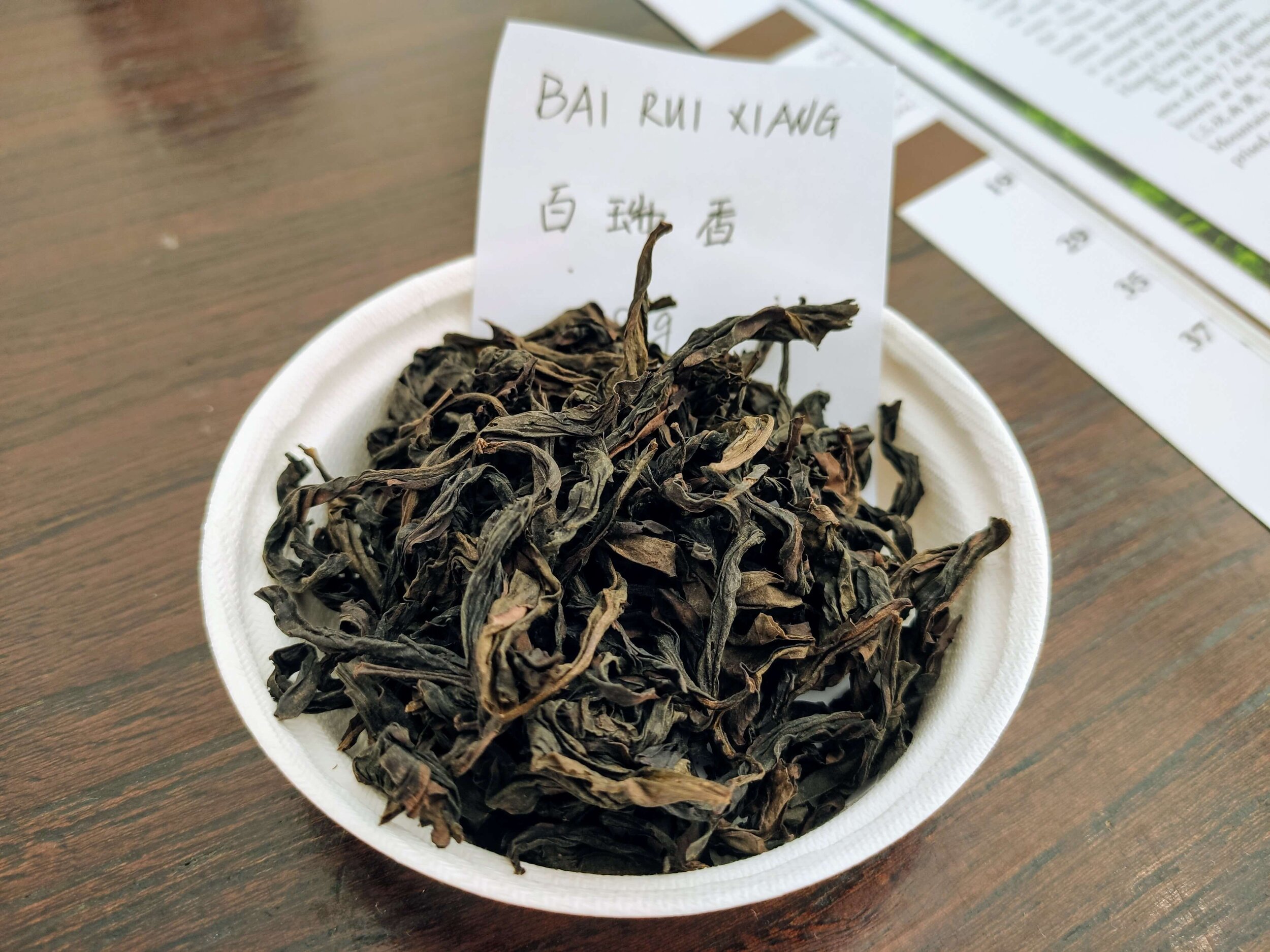

Bai Rui Xiang

Cliff Oolongs are known for their long lasting aroma and flavour over multiple brewings. Xin Yuan’s objective for the afternoon was to fit in an 8 brew tasting of one of the teas! So will Bai Rui Xiang or Hundred Harmonious Fragrances live up to its name and provide us with a different aromatic experience at every brew? In short, yes!

It’s been a while since I drank a Cliff Oolong and the smell of the wet leaves hit me square in the nose. I’d forgotten just how strong and punchy these teas are! The leaves turn a mixture of dark greens and russet colours, giving a dark amber liquor. The heavy roasted and toasty aroma is immediate, with hints of charcoal from the roasting. Then with each brew the smell changes, moving through to a sweet caramel.

The first brew gives a light roasted flavour which becomes much stronger on the second brew. It’s more robust with a drying sensation that coats the tongue. On the third brew, the mineral character comes through, again it’s drying. The aftertaste was a surprise, at the back of the throat, it’s like a thick chewy sweet with a fresh herbal sensation. The fourth brew is getting lighter with hints of charcoal and sweet molasses. Fifth brew is lighter again with a drying astringency and a slight charcoal aftertaste. The sixth brew is more sweet and silky. We went up to nine brews, and the last few were quite the same, being light, more easy going with the mineral, charcoal and sweet flavours balanced out.

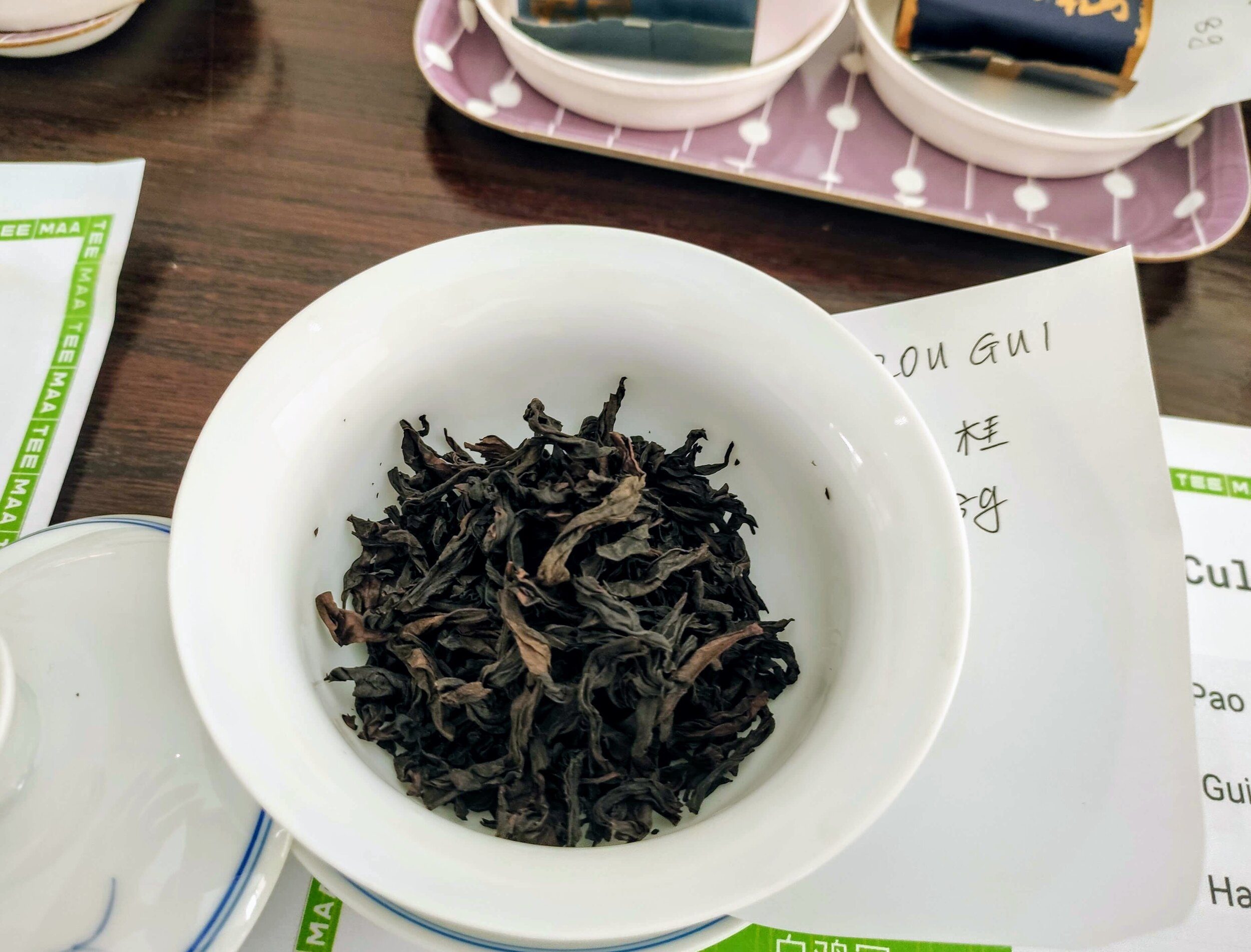

Rou Gui

We tasted the next two Oolongs, Rou Gui and Shui Xian, side by side over three brews to compare. Rou Gui is translated as Cassia which is Chinese cinnamon. However, I didn’t get the cinnamon aroma from this.

For me the aroma is more fruity than spiced as well as the distinctive smoky roasted smell. The roasted charcoal flavour is dominant, with nice juicy fruity currant notes. It has a thick drying mouthfeel and a long sweet aftertaste. This was definitely my favourite out of the two.

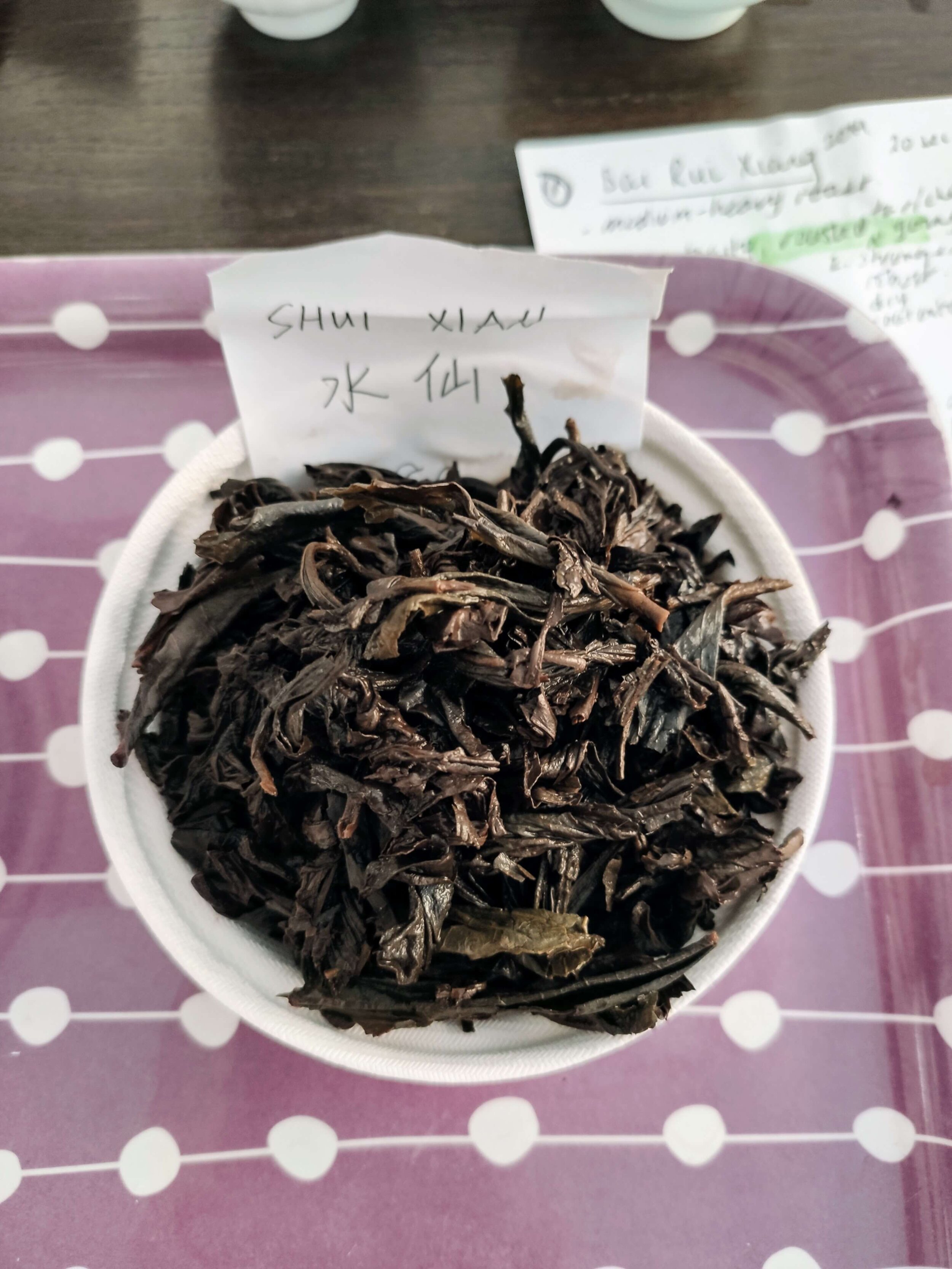

Shui Xian

Shui Xian is most commonly translated as Narcissus, but also goes by the names of Water Fairy, Water Goddess and Water Lily. To be honest, I had a really hard time trying to like this one! Once brewed up, its dark wiry leaves produced an incredibly pungent and sharp aroma, reminiscent of a farmyard. Strangely though, the jug that the tea was poured from had a very sweet floral fragrance.

Its sharp flavour put my mouth on edge at first! Certainly a robust strong and thick tea that coats the entire tongue. It leaves a long roasted charcoal aftertaste. I feel like there must be sweet floral notes lurking in the flavour somewhere, perhaps in later brews. Or maybe I need to start out with less leaf/shorter brewing time. Yep, hard to love you Shui Xian, but I’ll keep on trying.

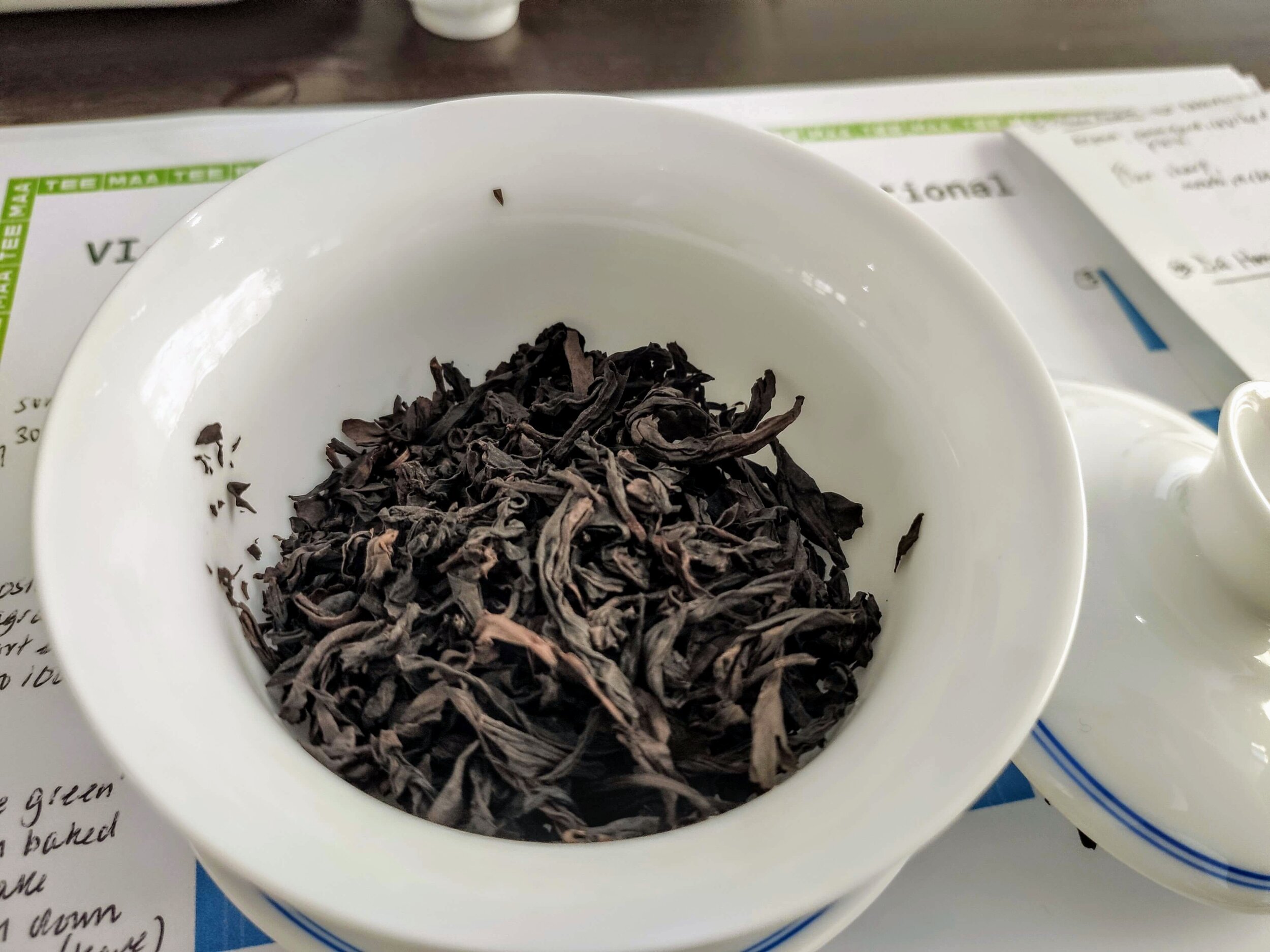

Da Hong Pao

And so to the most famous Wuyi Cliff Oolong, Da Hong Pao (Big Red Robe / The Emperor’s Crimson Robe).

It has lots going on in the aroma. At first, a pleasant roasted toasty smell, then somewhat coffee-like to me, with sweet caramel undertones. And later, jammy and fruity currants. It has a full bodied taste, with a good mineral character and toasty, sometimes fruity flavours. There’s a drying mouthfeel with a long pleasant aftertaste. I’d happily sip on this on a chilly autumn day.

Aged Da Hong Pao

Our final Cliff Oolong is a Da Hong Pao that has been aged for approximately 10 years. It seems that ageing completely changes a Wuyi Cliff Oolong, seeing it slip into a mellow old age. It’s much more akin to Pu’er tea, with a mellow earthy aroma. It doesn't really retain much of the characteristics of a fresh Da Hong Pao. The flavour is so much softer and more easy-going, and drinks like a nice Pu’er.

The very essence of a good Cliff Oolong is Yan Yun (Rocky Charm) and Yan Gu Hua Xiang (bones of rock and floral fragrance). I feel that age knocks out these very characteristics, smoothing off its hard gnarly edges and loosing its fighting spirit.

A note on Brewing Cliff Oolongs

As a reference, at the tasting Xin Yuan brewed 7.5g/8g of tea in 100C water. The first steep was 20 seconds, adding 10 seconds for each additional steep. She used a porcelain gaiwan (110ml) to capture the full flavour of the teas. An Yixing clay teapot can also be used for Wuyi Cliff Oolongs. Unlike porcelain, the clay is porous and will take the edge of some of the more sharp flavours.

In general the first brews of a Wuyi Oolong have a very strong roasted aroma and flavour. Some people prefer the later brews when the punchy roasted flavour has calmed down. With the later brews you can experience the different flavours (floral, sweet, fruity), textures and minerality coming through, depending on the cultivar.

Wet leaves: top row, left to right - Rou Gui, Shui Xian, Da Hong Pao; bottom row, left to right - Bai Rui Xiang x 2, Aged Da Hong Pao

Cliff Oolongs are famed for their long lasting aroma and flavour through multiple brewings. Retaining their Yan Yun (Rocky Charm) and Yan Gu Hua Xiang (bones of rock and floral fragrance), and remaining smooth beyond the eighth brew is the criteria for a high quality Cliff Oolong.

This was certainly a caffeine fuelled afternoon, we were all a little tea drunk by the end! I now have a selection pack of Wuyi Cliff Oolongs. We’re re-embarking on our rocky love story! Have you tried Wuyi Cliff Oolong tea?